The role of animals in regulating the carbon cycle is remarkable. But it doesn’t get enough attention in the rapidly growing discussion around carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

I was recently fascinated by an article from Mark Hillsdon at Mongabay News about “animating the carbon cycle,” or ACC. ACC is the essential role wild animals perform in controlling the carbon flows between ecosystems and the atmosphere. While it seems obvious, animals of all sizes influence nutrient cycling, surface water loss and evaporation, and composition of plants in various places. These interconnected critical processes, when observed on a global scale, can have a massive impact on avoided emissions and carbon removal.

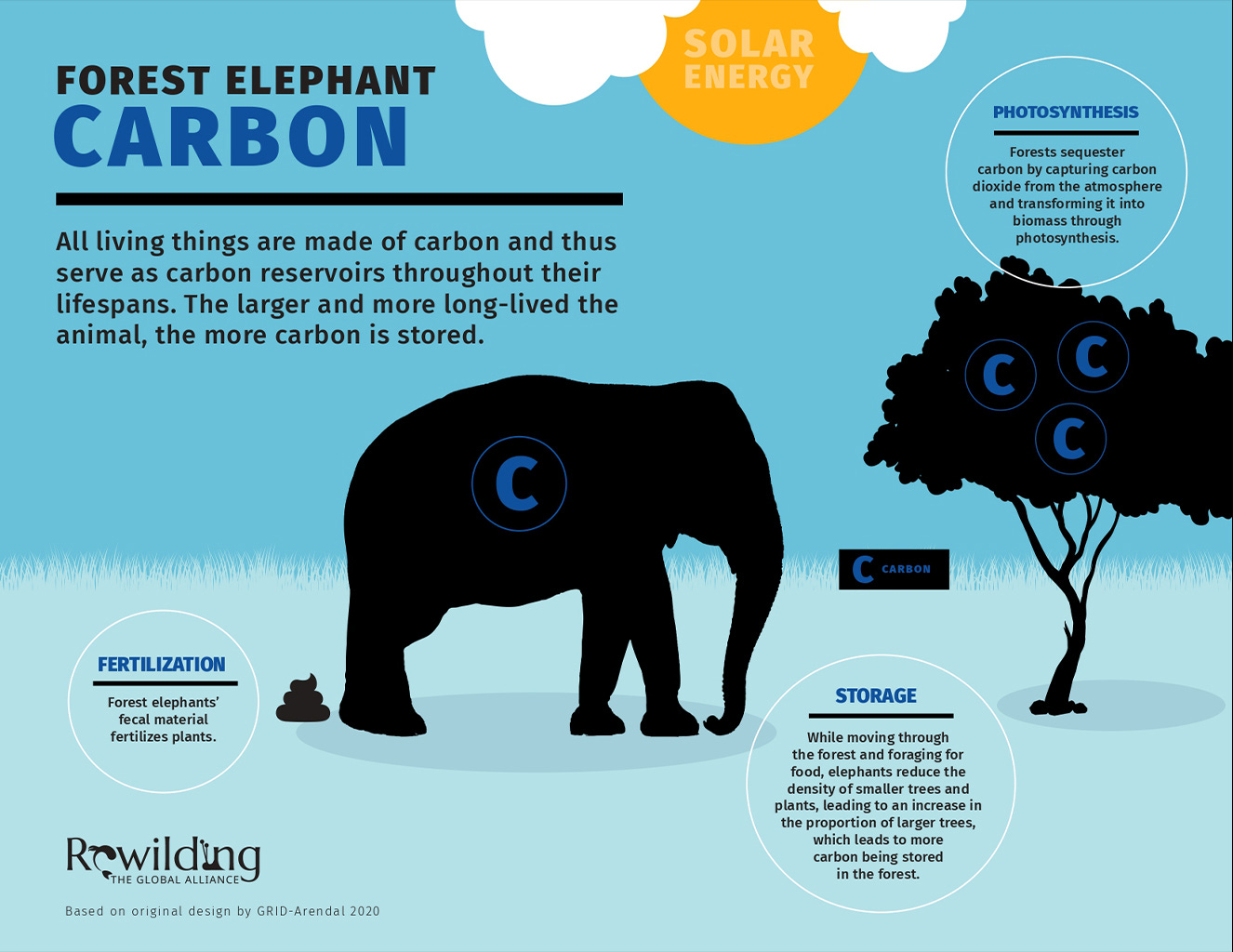

However, in order for these carbon benefits to ensue, we need more wildlife. Unfathomably (or not), wildlife populations are down 69% on average since 1970, due mostly to land use change that destroys, fragments habitats, and reduces biodiversity. That land use change, which has increased in scale over the past 30 years, annually accounts for over 10% of total global emissions. Adopting carbon tunnel vision for a moment, further destruction of habitats and species loss would have profound implications on the ability for rainforests, grasslands, tundra, and all other ecosystems to retain and remove atmospheric carbon dioxide. For example, the extinction of critically endangered elephants could cause the rainforest of central and west Africa, the second largest on earth, to lose between six and nine percent of their ability to sequester carbon.

We need to catalyze conservation and restoration efforts to bring wildlife populations back to historic levels. Understanding the impacts of animals on the carbon cycle promises a potential path toward making that a reality. If we can measure and report on emission impacts from additional conservation and restoration, we can direct more finance towards those efforts where it makes sense to.

But the question is, how? Can the ubiquitous (and controversial) carbon credit help fill the $700B+ gap in nature funding? Is it possible to design effective credits and monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems? What are the risks for negative unintended consequences with the further creditization of nature?

ACC in Practice

Animating the carbon cycle is incredible in reality. Animals and plants of all kinds have important (and at times overlapping) roles to play.

Predators Preventing Overgrazing

One of the main ACC functions is predators influencing grazing behavior, which has significant impacts on carbon storage in plants and soil. Grazing helps cycle nutrients in the soil as animals move from field to field, allowing grass to both regrow aboveground biomass and retain their root structure in the soil. We typically focus rotational grazing efforts on livestock. But what about the role of apex predators like wolves and lions, which often have the greatest impact on shaping an ecosystem? And predators of all shapes and sizes for that matter, such as:

Wolves hunting plant-eating moose in North America’s boreal forests

Lions patrolling the African grasslands

Sharks preventing dugongs from consuming excessive seagrass

Sea otters feeding on kelp-devouring urchins

Spiders forcing grasshoppers to feed on less carbon-rich grasses

Predators can prevent overgrazing by forcing herbivores to keep moving and graze across landscapes. Without such predators, the number of herbivores can increase excessively, potentially causing lands to become degraded and/or plant biomass to decrease sharply, along with their respective carbon sequestration.

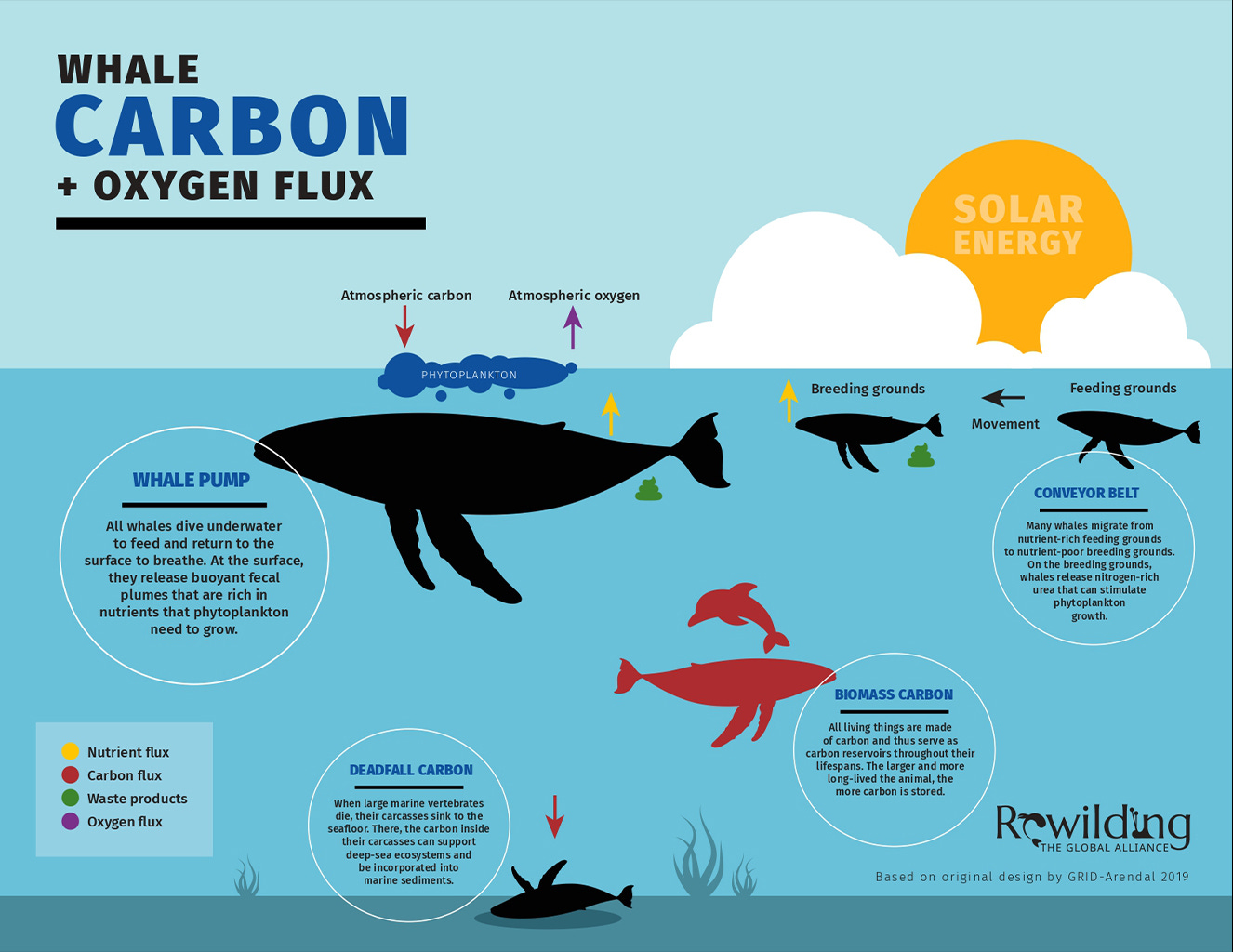

Nutrient Cycling & Biomass Storage

There’s also significant impact from large marine mammals like whales. Whales help naturally circulate nutrients like iron and nitrogen for the photosynthetic growth of phytoplankton. Plus, the sheer weight of their biomass is quite significant; as they die and decompose on the seafloor, their carbon matter supports deep sea ecosystems and can be incorporated into sediments for longer storage.

Avoided Wildfires

Though overgrazing is definitely an issue that requires the role of carnivores, elements of grazing and other behaviors from herbivores is essential to ensuring greater carbon sequestration.

Savanna ecosystems can contain a variety of easily combustible biomass, which under certain conditions, may cause expansive wildfires. Grazing behaviors from animals like wildebeests results in the consumption of that biomass (and fuel for fire) into dung, which both prevents further wildfire and increases soil organic matter. According to another Mongabay article by Tim Vernimmen, “scientists calculated that when wildebeest populations bounced back there after a 1960s virus epidemic, the avoided emissions from fire, along with extra carbon stored underground, allowed the vast grassland to absorb more carbon than it emitted.”

Seed Dispersal

One of the greatest traits of large browsing herbivores like elephants is their impact on seed dispersal. When elephants consume fruit from large trees, they leave the seeds behind in their dung, which enables new seedlings to sprout up. In fact there are some trees that are specifically adapted to disperse their seeds upon being shaken by animals like rhinos and elephants. Such dispersal (or perhaps reframed as afforestation) is important for improving the carbon-storing capacity of whole forests. Moreover, from a climate adaptation perspective, fruit-eating animals can spread seeds in a way that enables trees to “migrate” to locations more optimal for plant growth as the planet warms. However, with the number of wild, fruit-eating animals decreasing sharply, the ability of plants to move in sync with their natural climatic comfort zone has reduced by around 60%.

Forest Management

Elephants do much more than just dispersing seeds. They essentially provide the role of integrated forest management (IFM). To put it eloquently, Stephen Blake, Ph.D., says "Elephants are the gardeners of the forest. They plant the forest with high carbon density trees and they get rid of the 'weeds,' which are the low carbon density trees. They do a tremendous amount of work maintaining the diversity of the forest." Yet the populations of African savanna elephants are at less than a quarter of the density their ecosystems can sustain, which means there is plenty more carbon sequestration potential to be realized.

Albedo Effect

Some herbivores in arctic regions also have a significant impact on preventing further warming by keeping the albedo effect in check. As woody plants migrate northward due to warming temperatures, they bring with them darker foliage and shade (especially compared to snow-covered tundra), which attracts more sunlight and warming, kicking off a warming feedback loop. Large herbivores are important for consuming this biomass before it’s seedlings are able to migrate further north. In fact, Tim Vernimmen reported that the extinction of large plant-eating mammals, such as mammoths, may have increased temperatures in Siberia by up to 1°C.

The list goes on and on. There are significant impacts from many other types of land and ocean-based animals out there, which is invigorating and peaks the curiosity of what we still don’t know around the essential functions of our ecosystems.

The Possibilities of Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV)

What if we could wave a wand, and with high accuracy, measure the degree of carbon cycling and storage taking place as a result of animals in these natural systems? How would that impact how we evaluate certain wildlife restoration projects (aka ACC projects herein)?

There is a host of academic studies that have focused on making this a reality (many of which are cited in the two aforementioned Mongabay News articles). If we knew that by restoring wildlife populations we could remove an additional 1+ gigaton of carbon dioxide equivalent, wouldn’t we include directing finance toward ACC projects as part of the suite of nature-based CDR approaches? Especially, given the inherent biodiversity and community co-benefits that come with them?

In order to get to that point, we’d need an MRV system focused on community-grounded solutions while integrating combinations of soil sampling, biomass measurements, aerial imagery, fluxnet stations, satellite & ocean observation data, biodiversity monitoring, and modeling (see a list of potential companies that can help at the bottom!). It seems some of the tech exists but is being used for different types of projects and can possibly be tuned for these purposes.

For example, we are already conducting soil organic carbon testing on grasslands to measure the effects of cattle’s rotational grazing patterns. At the minimum, could we use a version of those same technologies and methods (soil samples, imagery, and modeling) to track how the growth in say, lion populations as a result of a rewilding initiative, leads to increases in soil carbon storage in the savanna? And that's just level one: more robust data collection from tools like bioacoustics and environmental DNA (as George Darrah writes about) can be integrated as credits begin to represent more holistic benefits vs. solely carbon-based impacts.

However, designing the proper MRV system is certainly a challenge. Many of the typical MRV issues around double counting, additionality attribution, and leakage seem particularly relevant to ACC projects and would require the right set of baselines, boundaries, and standard-setting. As an example in tropical forest regeneration, how would one account for additional carbon removal due to seed dispersal from reintroduced orangutans relative to other overlapping projects focused on reforestation?

Funding this MRV development is also a challenge. Similar to other MRV providers, it will require both grants for R&D and the existence of project and market demand to help providers raise the necessary capital.

Financing ACC Projects

We should absolutely continue tapping into existing means of financing conservation and restoration, such as policy and grant-making, as well as creative new alternatives like biocredits, debt-for-nature swaps, and conservation bonds. Yet today’s climate finance system is increasingly driven by carbon credits and net-zero goals. Ideally, we move to a future where net-zero is a box, rather than the box to check. And where businesses are critiqued and measured based on their Ecological Footprint rather than how many emissions they release and then “offset.” As I’ve written about previously in relation to soil carbon, due to the short-duration carbon cycles, risk of reversals, and MRV challenges, ACC projects in particular should be funded as beyond value-chain investments; not as offsets.

In a similar vein, I recently spoke with Eric Wilburn, who suggested the concept of requiring companies to report on two metrics: 1) reduced emissions through internal decarbonization efforts and 2) total or % of profit spent on climate contributions. Within this framework and second bucket, companies could be more empowered to contribute beyond value-chain mitigation toward climate endeavors such as wildlife restoration.

But until then, we have a) carbon credits, b) very early-stage biodiversity credits - which I am bullish on, c) reliance on philanthropy and government spending, and d) a massive financing gap for conservation of ecosystems and carbon sinks.

Cautions of Credits

However, there are clear issues with ascribing financial credits to nature, due in part to the sheer complexity and interconnectedness that ecosystems possess. Alexa Firminich writes of the unequivocal dangers in a very real way and notes the following:

“There is rising concern among civil society, NGOs, think tanks, indigenous peoples, local communities and several leading economists, that this rapid encroachment of financial markets into nature is a harbinger of dangerous times to come. They foresee this solutionism as yet another wave of neo-colonial extraction, rent-seeking behavior, speculative volatility, inequality perpetuation, and a further impoverishment of our spiritual relationship to other life…

The financial system is a powerful global coordination mechanism that should be used to catalyze resources into the regeneration of nature. But the wave of developments in nature-based securitization such as credits, bonds, offsets and ecosystem service payments must be paired with a parallel evolution in other domains.”

There are significant unintended consequences that can abound from new ACC projects, such as adverse ecosystem impacts from improper rewilding, the commodification and valuing of one species over another, elements of green colonialism and land grabbing, corruption from special interests, and many more. Alexa’s article goes on to introduce potential governance mechanisms to design into the various nature-based solutions and market structures backing them, which is worth a read. At the center must always be the rights and interests of local stakeholders, which includes not just humans but animals and other natural beings.

Path Forward

Even with the best intentions and frameworks, there’s always risk of negative consequences. But in our current global order, ascribing a financial value to ecosystems appears essential to funneling resources toward their respective conservation and restoration.

We need to bring back wildlife populations to their historic levels for the sake of climate mitigation, biodiversity, and community well-being. And funding ACC projects is an promising pathway to do so. It’s worth exploring the funding and implementation of these wildlife restoration projects further through more research, designing MRV solutions and accounting standards, and engaging with frontline communities to co-design and fund pilots. Rebalance Earth has begun leading the way with the first nature credits for elephant conservation, and it will be exciting to see how the opportunities continue to unfold.

Thank you to George Darrah for the insightful feedback. A non-exhaustive list of companies that could potentially support the necessary measurement and reporting efforts for ACC projects include:

Community focus: Cyber Tracker, Earthshot Labs, and Open Forest Protocol

Soil sampling: Yard Stick, Haystack Ag, enrichAg, Earth Optics

Aerial imagery: Bioverse, Wildlife Drones

Fluxnet stations: CarbonSpace and Quanterra Systems

Satellite data: Planet, Pachama, Vibrant Planet, Boomitra, Albo Climate, Perennial, Seqana

Biodiversity monitoring: NatureMetrics, Pivotal Earth

On the seed dispersal note- I also know there are certain types of seeds that must pass through (particular?) animals' digestive systems in order to strip a coating off that allows the seed to germinate. I don't have specific examples for high carbon density trees but I'm guessing they're out there.

Hi Mitch,

Thank you for your essay bringing attention to the role ruminants can play in soil carbon drawdown.

While much of what you write is correct, a number of important points and nuances are missed.

First, we absolutely do need more wildlife.

"This once was a world that had 10 times more whales; 20 times more anadromous fish, like salmon; double the number of seabirds; and 10 times more large herbivores — giant sloths and mastodons and mammoths," Roman said.

No Crap: Missing 'Mega Poop' Starves Earth

October 26, 2015

https://www.livescience.com/52587-missing-giant-poop-is-hurting-earth.html

What many scientists don’t yet realize is that properly-managed livestock must be used to heal degraded grasslands and savannas to create favorable conditions under which wildlife populations will thrive.

Leading conservation organizations throughout the world are using well-managed grazing of livestock to heal degraded soil, restore wildlife habitat, replenish dried-up rivers, and sequester carbon.

“To me, Allan [Savory]’s results are spectacular. Despite recent drought, [Holistic Planned Grazing] has transformed this ranch from desert to rich grassland. Today, the grass holds the water, and streams that were dry for decades are flowing again ... it could be the best thing, the absolute best thing, conservation has ever discovered.” — Conservation biologist M. Sanjayan, PhD, CEO of Conservation International and former lead scientist of The Nature Conservancy

(2015, 2 mins.)

https://youtu.be/XfPpC258ZwM

See examples below of conservation organizations utilizing regenerative grazing to improve wildlife habitat.

Second, as discussed in this two-part interview, wild animals, although essential for ecological health, cannot be used for regenerative grazing. This was discovered by Allan Savory in the 1970s after he tried doing it for several years then stopped after it became apparent it wasn’t working.

Regenerating Civilisation: Allan Savory on holistic management, scaling & a sense of survival

(Dec. 1, 2020, 1 hr. 17 mins.)

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-regennarration/id1236423380?i=1000500922110

The Domino Effect: Allan Savory on addressing the cause of climate change, megafire & desertification

(Dec. 1, 2020, 36 mins.)

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-regennarration/id1236423380?i=1000500933513

Third, the role of predators is to keep grazers bunched into a herd. However, predators do not keep the herd moving across the landscape. Rather, repulsion to dung and urine on sullied grass is what keeps the grazing herd continually on the move in search of fresh forage. In addition to preventing overgrazing, this repulsive effect is responsible for keeping the herd from re-visiting the same area to graze again until enough weathering happens to dispel the manure and odor. In turn, this long recovery period allows the grass (i.e., grasses, forbs, legumes) to re-grow fully before it is re-grazed.

Fourth, Rotational Grazing, a calendar-based method of animal movement, does not provide the flexibility necessary to regularly change animal movements based on the vicissitudes of varying temperature, rainfall, sunlight, etc. Instead, to be optimally effective, plant height must be monitored regularly and animal movements either sped up or slowed down in response. This precision is the reason why Holistic Planned Grazing, aka Adaptive Multi-paddock Grazing, is dramatically more effective than Rotational Grazing which, under certain circumstances, can be deleterious to ecological and soil health.

“Unlike rotational grazing which adheres to a calendar, [Holistic Planned Grazing] involves moving livestock in response to information gained from monitoring the land and animals. Decisions are ‘determined by the plant growth, constantly monitoring and adjusting... allowing for recovery time at the end’”

Climate change mitigation as a co-benefit of regenerative ranching: insights from Australia and the United States

Gosnell et al. 2020

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsfs.2020.0027

This semantic distinction is clouded by the fact that the definition of Rotational Grazing appears to be shifting, such that when some graziers say they are doing “Rotational Grazing” they are actually doing Holistic Planned Grazing (i.e., using a grazing chart to plan, monitor, and adjust animal movements). Frankly, the terminology is a mess. This is a key source of the confusion by some academics concerning regenerative grazing.

Lastly, the best Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) approach to ecological restoration I am aware of is the Savory Institute’s Ecological Outcome Verification (EOV) protocol.

https://savory.global/eov/.

Burberry and New Balance are among more than 200 corporate partners in the Savory Institute’s Land to Market program, based on its EOV protocol.

https://www.burberryplc.com/en/news/sustainability/2021/burberry-builds-on-climate-positive-commitment-with-biodiversity.html

I hope this information is helpful.

The following resources may be of interest.

If you have any questions, I would be glad to discuss this matter with you.

Best wishes,

Karl Thidemann

Cofounder, Soil4Climate

Hope Below Our Feet: Peer-Reviewed Publications on Well-Managed Grazing as a Means of Improving Rangeland Ecology, Building Soil Carbon, and Mitigating Global Warming

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1QR9Xk3aq3soidmob6nS9PMstKcllmRlgpaVDyFzRkwY/edit?usp=sharing

Regenerative Agriculture Seminar - Dr. Richard Teague With Q&A - CSU Chico Media

(2017, 1 hr. 32 mins.)

https://media.csuchico.edu/media/t/0_3bfb9gsm

Allen Williams, PhD - Restore Soil and Ecosystem Health with Adaptive Grazing

(2018, 42 mins.)

https://youtu.be/BwH6od6Jaq8

Note: Adaptive Grazing is short for Adaptive Multi-paddock Grazing, a term used by some academics to describe Allan Savory’s Holistic Planned Grazing.

Soil Carbon Cowboys

(2013, 12 mins.)

https://youtu.be/MDoUDLbg8tg

More videos on regenerative grazing at ...

Carbon Cowboys Film Paddocks

https://carboncowboys.org/

HOW WE PLAN OUR GRAZING - Richard Perkins

Filling in a Holistic Planned Grazing chart

(2020, 1 hr. 21 mins.)

https://youtu.be/rO7xl9l-YRs

Holistic Planned Grazing Chart for Livestock Management

Heifer USA

(2021, 8 mins.)

https://youtu.be/1wVAH9PkiHQ

Holistic Management, Third Edition: A Commonsense Revolution to Restore Our Environment – Allan Savory, Jody Butterfield (2017)

Holistic Management Handbook, Third Edition: Regenerating Your Land and Growing Your Profits – Allan Savory, Jody Butterfield, and Sam Bingham (2019)

The National Audubon Society created its Conservation Ranching program in response to steep declines in grassland bird populations.

What in the World is Conservation Ranching? Your guide to Audubon's program to make cattle ranching prairie- and bird-friendly

October 2, 2017

https://www.audubon.org/news/what-world-conservation-ranching

“A healthy beef industry is an important conservation partner, and with their support, enables us to conserve what’s left of Canada’s grasslands,” said the letter from groups such as Ducks Unlimited, Birds Canada and the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Canadian Conservation groups rally behind beef sector

June 16, 2020

https://www.albertafarmexpress.ca/news/conservation-groups-rally-behind-beef-sector/

“WWF-Australia works with innovative beef producers to develop, trial and validate improved livestock and pasture management that can deliver significant economic, social and environmental gains. Our major objectives are to reduce sediment in stormwater run-off from farms and improve water quality in the catchments feeding into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, while also conserving habitat for wildlife on farmland.”

Project Pioneer - WWF-Australia

September 2020

https://www.wwf.org.au/what-we-do/food/beef/project-pioneer#gs.f72u9y

“The results of this study show a potential win-win situation for the Pantanal and Cerrado’s ranches and wildlife,” said the study’s lead author, Donald Parsons Eaton of the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Grazing as a Conservation Tool

May 3, 2011

https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/5106/Grazing-as-a-Conservation-Tool.aspx